Let’s Gather In

How can the long-history of rural communities inform rural innovation today?

Our rural communities are in a state of transition. Once dominated by agriculture, they have now become as economically diverse as urban economies: in England, rural areas house 17% of its population, but 24% of all its registered businesses. Rural England also covers around 90% of the land, a key factor in the uneven experience of services, infrastructure, and opportunities ¹. Loss of local services and increased social isolation, for example, reflect persistent drivers of rural disadvantage (e.g. ²). New types of action are called for to support thriving rural communities. These need to be locally rooted, accountable, and work to the wider benefit of all. Place-based responses might include new voluntary groups, community enterprises community, or action to rebuild social and economic capital.

1. House of Lords Select Committee (2019). Inquiry Report: Time for a strategy for the rural economy. London: HL Paper 330.

2. Somerset Community Foundation (2019). Hidden Somerset: Rural Isolation. Shepton Mallet: Somerset Community Foundation.

A Wicked Problem

A classic wicked problem, interactions between public policy, local initiatives, and grassroots activism often result in haphazard or patchy responses to real-world challenges. A clumsy solution might ask how communities can be supported to identify shared needs, how individuals can be empowered to lead on new responses, and how shared insight might be meaningfully scaled. With this in mind, supersum approached The Churches Conservation Trust (CCT), a nationally operating charity with over 340 historic churches at risk. Long at the centre of communities, these sites have faced uncertainties across the centuries. We argue that these historic sites can play a major role in the creation of distinctive place-making activities at scale. Further, that it is their exceptional, out-of-the-ordinary nature that matters most in tapping into their transformative potential. With the CCT, we want these are sites to be enjoyed by everyone as places of heritage and spirituality, but also to support community, social, and economic life.

“The long-term survival of Church of England church buildings requires a change in the way many communities regard these buildings. To survive, a church building must be both valued by, and useful to its community”

3. The Taylor Review: Sustainability of English Churches and Cathedrals (2017). London: DCMS.

The Story So Far

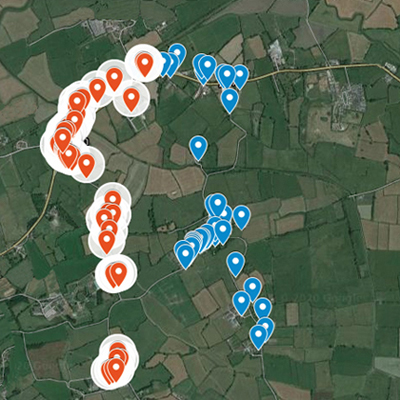

Whilst our long-term goal is to develop new regeneration models that can activate CCT sites in response to shared community needs, there are many steps needed to achieve this. Our first step is working with a small number of communities at rural CCT locations to build a picture of rural life today and explore how the long-history and long-reach of community life (back to the medieval period) can inform the way we think about rural innovation today. This work is supported through funding from the University of The West of England and the Brigstow Institute at the University of Bristol.

Our Approach

Project Partners