Tim Senior

Stuart McClean

What future for our underused churches?

Our empty rural churches are in the news again – a poignant symbol of our heritage at risk and the changing nature of rural communities. Faced with the question – what future for our underused churches? – we argue that safeguarding our built heritage and creating vibrant rural life go hand-in-hand. There is no elegant solution to making this happen. It calls for clumsiness. This blog post introduces supersum’s most recent work under the Gather In project. We have now published an academic article – Medievals and Moderns in Conversation – in the open-access MTI journal special issue on collaborative responses to cultural heritage in communities. In this paper, we describe our work in Brockley, North Somerset, to make sense of rural life today and develop a clumsy place-making strategy for imagining a new future for their medieval church.

Churches past and present

The historic medieval parish church played a central role in the formation of ‘community’ as we might still recognise it today. The parish embedded individuals into new types of social network, was a generator of local infrastructure, business credit and education, and the principal driver behind creative and cultural life. Once numbering over 12,000, parishes in the medieval period have been described as the “micro-laboratory” of new political structures in the country at large, supporting the transition from a feudal to post-feudal society. We argue that our historic churches can be living labs once more, deeply responding to the needs and strengths of communities around them, mirroring their historic social role. What’s key is responding to communities not as they have been in the past, but as they are today. The scale of this challenge, and the value of responding to it well, is considerable. Of the 15,700 Church of England churches, 57% are in rural areas with 91% of those listed historic buildings. Most face a similar challenge: finding a new social purpose whilst also safeguarding valuable built heritage.

St Nicholas, Brockley

A wonderful medieval church with great potential

A Wicked Problem

There is no elegant solution to this challenge. There are many different voices involved – from local residents, congregations, heritage organisations, Parochial Church Councils, local government etc… – each with their own sense of why church buildings do (or do not) matter, and what place they should hold in communities today. Conventional solutions will not work for everyone. Taking one dimension alone: preserving buildings as ‘built heritage’ diminishes their potential to be used in new ways; repurposing buildings (often by stripping out interiors) cuts those historic ties and can be costly to deliver. For historically significant churches, options available may seem few and far between.

Our first step has been to take a step back: rather than facing this as a ‘crisis of the present’, we have asked what might be learned from the long-history of churches – one of continual change and adaptation over centuries. This long-history reveals not only forms of continuity with historical communities, but uncovers a richer repertoire of ideas around church use and community vibrancy. We argue this sets the scene for a more pluralistic (clumsy) response to the challenge of our underused historic churches.

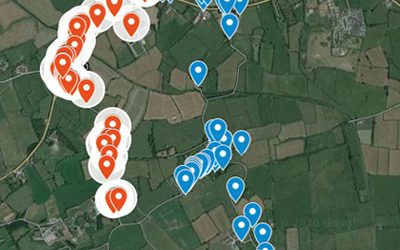

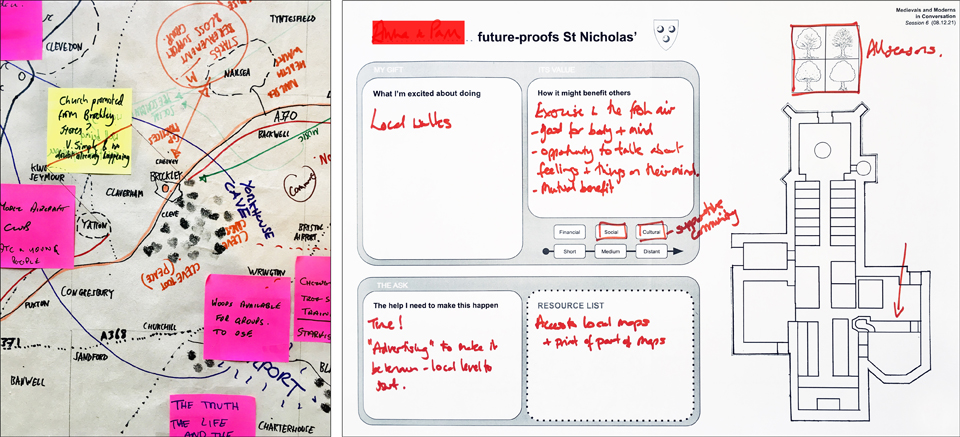

Workshop materials

Mapping parish assets and working with a ‘future proofing’ canvas

A Clumsy Trajectory

The journal article outlines our work with residents of Brockley, North Somerset, to explore what community ‘looks and feels like’ today. We use Cultural Theory (see blog post here) to describe how different ‘ways of life’ interact to shape that sense of community. What has emerged from this work is a clumsy placemaking strategy, one designed to get more people onboard with using the church in a way that benefits the whole community and helps safeguard the church as built heritage. It’s a clumsy strategy because it tries to get different ways life – sometimes at logger-heads with each other – to work more productively together.

First and foremost in this strategy is changing the narrative about community ‘ownership’, recognising the much richer and diverse associations that connect people together with their church. Second is working to replenish much-needed social assets (centred on the church itself) by working with entrepreneurial individuals within and beyond the community. Third is the development of alternative decision-making structures for the church’s Friends group, partially ‘inverting’ committee hierarchies that can no longer respond in an agile way to the community’s needs and strengths. Finally, is positive action to bring new voices into church futures, particularly those who might think this impossible.

A storytelling device

‘Slow technology’ that associates tangible tokens with digital audio recordings (based on Jigasaudio)

Learning from long-history

The central focus of our paper is how a clumsy placemaking strategy might be built on the foundation of a church’s long-history. Our workshops together at Brockley have recognised how the historic parish church served multiple different roles at the centre of community life, encompassing social service, education, creative and even commercial activities, in addition to its central purpose in Christian teaching. As such, church spaces were historically ‘for everyone’ – a microcosm of the societies that sustained them and had need for them. In this way, even a rural church would be looking inwards and outwards, foregrounding family and kinship relations, shaping community identity, building interactions with other parishes and beyond (e.g. through trade, apprenticeships and festivities). The long-history of this particular church’s patron saint (St Nicholas the Wonderworker) is a stark reminder of how dynamic and historically contingent patronage can be – one that finds new expression as communities themselves find new expression. Finally, the concept of circular time (so different from the ‘social acceleration’ that dominates lives today) proves important – the cyclical patterns of worship, seasons, festivities, and life itself that give grounds for hope when you feel the world accelerating away from you.

What’s next?

This paper marks a key point in the development of the Gather In project, a proof of concept that clumsy solutions can help find a new way forward. In the current phase of the project (funded by the Economic and Social Research Council), we are expanding our community engagement to further develop the placemaking strategy and collaborate on new resources for ‘changing perceptions’ of historic churches. A small Seedcorn grant at St Nicholas’ Brockley will help demonstrate the untapped potential of the church and support the Friends of St Nicholas to map the value created with, for and by the community.

–––––

With thanks to our project partners in Brockley and our multi-university and multidisciplinary academic team, including Tom Metcalfe, Stuart McClean, Alexander Wilson, Simon Bowen, Marianne Ailes, Harri Hudspith, Lauren Cole and Sarah Wordsworth. We would like to thank The Churches Conservation Trust (particularly Ed McGregor) for supporting our work at Brockley.

The paper is ‘Medievals and Moderns in Conversation: Co-Designing Creative Futures for Underused Historic Churches in Rural Communities’ part of the special issue on ‘Co-Design Within and Between Communities in Cultural Heritage’ edited by Dr. Laura Maye and Dr. Caroline Claisse.